The Truth Behind Thanksgiving

- Jolene Anderson

- Nov 19, 2020

- 3 min read

Written by: Jolene Anderson & Bella Velazquez

For many Americans, Thanksgiving is a holiday to gather with family, eat good food, and give thanks. Most have heard the story behind the holiday. The Pilgrims left England for America seeking religious freedom on their ship, The Mayflower. When they landed at Plymouth Rock, they were faced with a terrible winter, many of them dying from the disease, starvation, or hypothermia. The following spring they met a local Native, who then brought his friend Squanto who spoke English. Squanto taught the Pilgrims how to survive by showing them how to properly plant, hunt, and gather. That fall, the Pilgrims invited Squanto and his village to have a feast to celebrate their first successful corn harvest, and it lasted three days. The only problem is that a lot of this story is historically inaccurate.

According to The Mayflower Society, it is true that the Pilgrims left

England seeking religious freedom, first in

Holland, then in what is known as the

The United States of America. They finally stepped foot in the New World in December of 1620. According to Plimoth Plantation, during the first winter, half of the original pilgrims died from disease.

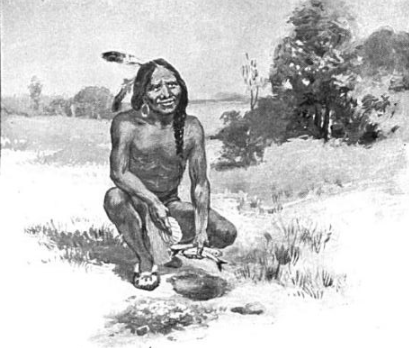

In March of the following year, they met Squanto. Squanto was a member of the Pawtuxet tribe when he was stolen from his homeland years earlier and sold into slavery by an English sea captain, eventually making his way back to America. Squanto helped the Pilgrims by teaching them how to farm, hunt, avoid poisonous plants, and help forge an alliance with the neighboring Wampanoag tribe. In November the Pilgrims invited the Wampanoags to celebrate their first corn harvest, lasting a total of three days. After that, the celebration was forgotten about until George Washington and his successors dedicated one or more days to give thanks. It wouldn’t be until 1863 when Abraham Lincoln officially declared it a national holiday

Minarets history teacher Robert Kelly confirms this assessment. “When I came down to it, was the story of Thanksgiving real? It is very much a myth.” He explains the story most people hear is the simplified or idealized version that second-graders are told. The story, in a way, glorified the U.S. as being peaceful when, in reality, the Wampanoag were killed or sold into slavery. He also says that although the myths are misleading that he enjoys the message behind the holiday and that it brings people together despite religion.

Ben Regonini, another Minarets history teacher, explained the differences between a modern-day Thanksgiving meal and what would have actually been consumed at the first celebration. “It would have been more quail or smaller animals. Turkeys would have to be dangerous to hunt, as that sucker's going to scratch you up pretty bad. American style food, like stuffing, was not a thing.”

When asked about how much of the true history she knew, junior Kayla Velazquez admitted, “I don’t know much about it. I haven’t really looked into it... my mind goes from Halloween to Christmas automatically, and the only reason I celebrate it is for the food.”

History teacher Katie Morgan said her favorite part of Thanksgiving is the message it gives of being thankful, even if the stories are not entirely historically accurate. She acknowledged the Thanksgiving myths like buckle hats, the menu, and other traditions. “In fact, it wasn't a national holiday until President Lincoln declared it as so during the Civil War to help unite the country,” said Morgan. “Before that, individual states would celebrate a day of thanks at their own discretion.”

As the popular holiday approaches, keep in mind the myths and realities of what truly happened hundreds of years ago. It is correct to associate Thanksgiving with Pilgrims and Native Americans, but the story deserves to be set straight, both for the sake of Wampanoag descendants and future generations who may be fed a false depiction of America’s history.

Links for the Pictures:

Comments